DNA Testing of Apple Varieties

DNA testing has truly come a long way in the last few decades, with huge benefits to human and animal health. With ever-improving of testing methods and economy of scale, DNA testing methods have now extended to detailed analyses of plant characteristics. Of particular interest to HFS is the possibility of verifying the identities of fruit varieties in our collections. Until now, we've had to rely on inexact identification methods such as flowering times and fruit characteristics. But DNA-based databases such as those at https://www.fruitid.com are starting to provide clear and reliable identities and parentages for many fruit varieties.

To give some examples, here are a few newly-found discoveries regarding apple variety relationships:

- Ribston Pippin is often referred to as a parent of Cox Orange Pippin ... but it actually isn't

- Granny Smith is usually assumed to be a parent of Red Granny Smith ... but alas, it is not

- Chains of apple variety generations are gradually becoming apparent: Devonshire Quarrenden is a parent of Worcester Pearmain, which along with James Grieve is a parent of Lord Lambourne

Your author has been reading up on this subject lately, and here attempts a simplified description of the most commonly-used methods for studying apple tree DNA. I'm trying to avoid using some of the more technical terms here; in fact, there are differences in the terminology and some of the methods used world-wide anyway. From what I've read, though, there's an increasing recognition that identification results should aim to be internationally comparable.

The usual method of obtaining a fruit tree's genetic material goes something like this: ground fresh leaves are chemically treated, the output of which undergoes PCR tests, similar to those used in COVID-19 testing, to magnify targeted genes. Genetic analysis on this then yields details about these genes, including the length of 'junk' (apparently nonfunctional) nucleotides between identified functional ones known as 'markers'. The count of nucleotides in 'junk' sections between marker pairs is commonly referred to as an SSR (Simple Sequence Repeats).

SSR counts between known marker pairs are a very useful variety-identifying characteristic, as they are not under evolutionary pressure to change randomly between generations. Typically one of a variety's parent's SSRs between specific marker pairs appears among the offspring's SSRs for the same marker pair too, although in some cases the length differs by a small number. Statistical analysis of SSRs for a number of marker pairs - typically eight or more - provides an excellent 'fingerprint' for a variety.

Important too is an apple variety's plody, a beautiful word which describes the number of copies the variety has of the 17 apple chromosomes. Most apple varieties are diploid (with a plody of 2), meaning they have exactly one copy of both parent's chromosomes, but many are triploid (plody=3) and a few are tetraploid (plody=4) and thus have more than one of these.

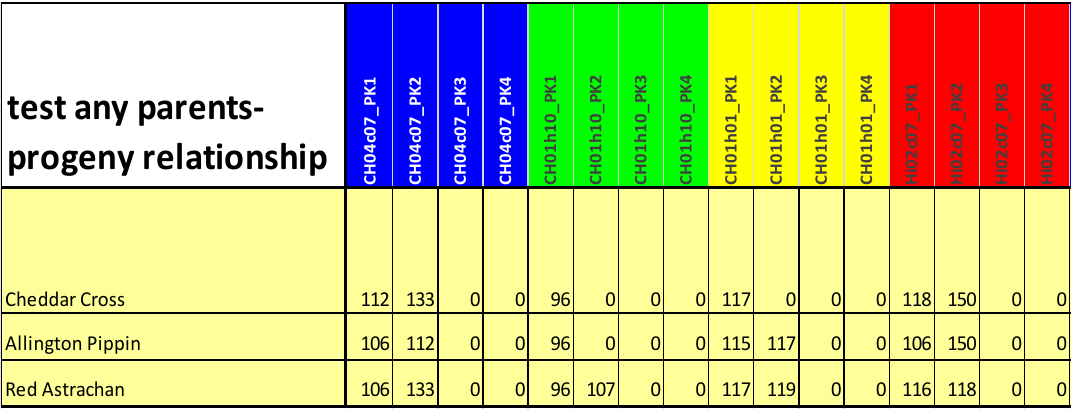

To illustrate some of the details described above, the following image shows SSR

analyses of four marker-pairs in apple variety Cheddar Cross, whose

parents are Allington Pippin and Red Astrachan. All three of these

varieties are diploid, which is why only two non-zero SSR values are

given for each of their marker-pairs. In almost all cases, at least one of the parents' SSR values are replicated in those of Cheddar Cross. Confidence in determining relationships like this improves with more such pairs being compared.

The price of such analysis is still about $50 per variety in the UK, though this is slowly decreasing. We don't know if apple-specific DNA testing is available here in Australia yet, but we're keen to find out. This is important, given that HFS plays a significant role in maintaining these for future generations - and we have reason to believe that some of our trees may be incorrectly identified. If you or anyone you know have access to plant DNA testing, or could be interested in taking on a horticultural project of social and historical importance, we'd love to hear from you!

Much, much more information in this area is available online, and growing rapidly. For the average reader (this author included), a lot of this makes fascinating but heavy reading, so keep the coffees handy. Here are a few sites which seemed the most informative and understandable:

- DNA identify/origin/parentage tables, mostly of UK fruit varieties: https://www.fruitid.com

- Readable and illustrated description of how DNA analysis on apples works: https://glosorchards.org/home/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Malus-Parentage-from-DNA-for-GOT-15Sep20.pdf

- Background on DNA analysis methods: https://www.asiaresearchnews.com/html/article.php/aid/4463/cid/2/research/science/riken/identifying_fruit_tree_and_ornamental_plant_varieties_using_dna_marks_.html

- How apple variety parental research is progressing: https://www.marcherapple.net/research/dna-parentage-investigation/

- Discussion over a one-tube reaction kit for apple SSR genotyping: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0168945220303745

Happy reading!

Fred Surr - August 2022